And, as always, we’re the last to know that Pierre has Monday off.

There’s a quick scramble to reschedule a number of Pierre’s other classes so that we can stretch the 3-day long weekend to an even longer 6 days, and we go back and forth on where exactly we should travel to. To fly or not to fly is our big question.

Not flying = 13+ hours on a train or bus to get anywhere dramatically different from the province we live in.

Flying = 2 hour bus to the airport + a 2 to 4 hour flight to get almost anywhere in the country, and isn’t very expensive compared to Canada. Distance-wise, it’s a bit like popping up to Winnipeg for a few days before flying home to Ottawa.

Xi’An is a major tourist destination for the Chinese – lots of history here. Things look pretty quiet at certain times of the day just outside our window facing the Bell Tower :

…but due to the long weekend, the city is usually packed, especially towards evening. The night we arrive, we head out of our very central hostel and land ourselves in foot-traffic gridlock. We shuffle around with the rest of the herd for the rest of the night, up-down-in-out of the subterranean walking tunnels, and through the Beiyuanmen (BAY-yoo-en-MEN) walking street.

At the head of the street is the Drum tower…

We lose the sound as we head into the crowd, past the tables with mounds of walnuts, almonds, dried kiwi and persimmons, and into a few restaurants. Xi’An is known for the excellent and inexpensive Muslim food, which can all be found on the Beiyuanmen walking street, which is the heart of the Muslim Quarter. There are cold noodles in sesame sauce, lamb kebabs, fried meat in pita buns. But the dish that has me at hello is the yang2 ro4 pao4 mo2 (羊肉泡馍) (sounds like: yang ro pow moe, rhymes with “hang no cow toe”).

Pierre isn’t quite as smitten with it as I am, though he too likes the chopped flatbread mixed in with mutton, broth, noodles and green onion. The North has a reputation for loving spicy and flavourful food and, true to form, the dish comes with hot chili flakes and half a clove of pickled garlic. Each bowl is about 2.50 $CAN. We eat it all, including the garlic, and top it up with a glass of fresh sour plum juice for 20 cents.

This part of China has a large and proud Muslim population. (The guidebook section on Xi'An refers to them as the Hui [hway], but every other mention of them refers to them by ethnic group, the Uighurs. At the moment I'm not sure what the distinction between the two terms is, so I'll keep using "Hui".) While this group is represented in other parts of the country as well – most easily recognized for their white caps (men) and black head dress (women) in the pulled noodle shops that are the traditional Hui business – the Hui have a very strong community here, including one of the largest mosques in China, tucked back in the narrow alleyways.

The mosque was founded back in the 8th century, though most of the buildings are from the past several hundred years. The architecture is very Chinese, so without the guide book we would never guess that this is a mosque.

The central minaret is shaped like a pagoda:

However, a few doorways have a bit more Arabic influence with calligraphy over the doorways, and a few onion-domed doorways:

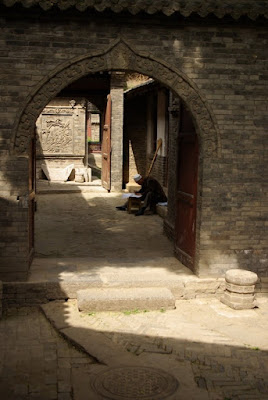

A short walk away from the mosque is the Folk House, a restored residence that is about 300 years old. I have a hard time thinking of the building as a “folk” house, since the owners of it were wealthy bureaucrats. “Folk” is one-bedroom. This is a sprawling area in the center of the city with room after courtyard after room.

We walk through the reception rooms and bedrooms, through narrow passages past round doorways and carved walls:

We assume that the majority of our trip will revolve around old houses and historic buildings, but we accidentally round out our sightseeing with something more modern when we come across the building/museum which acted as the Communist Party headquarters from 1937 - 1946. The building grounds are simple and clean, painted white with grey trim.

The ground level rooms consist of boardrooms/dining rooms, supply rooms and tiny austere bedrooms. These rooms typically consist of a bare wooden floor, whitewashed walls, a narrow army cot, a writing table and a plaque which describes which of the founding communists lived and worked in the rooms. Rooms in the basement house telegraphs, dormitory rooms and a clinic.

Bethune seems to be far more famous in China that he is in Canada. Mao wrote a glowing essay in his honour, and Chinese kids still learn about him in school. Bethune has statues dedicated to him, is buried in the Revolutionary Martyrs’ Cemetary, and has a medical university named after him.

A few Chinese tourists come across us in the clinic, and when we answer “Canada” to the inevitable question as to where we’re from, they're very excited as they tell us that "Bai2 Qiu2 En1" (白求恩) was Canadian too. We take a round of photos together. (The woman standing next to me was actually quite cheerful and excited to have her picture taken, though you can’t tell from her face in the picture.)

In between our trips to various sites in the city, we decide that we should dedicate Day 181 to the Terracotta Warriors. Since we plan to leave town and visit another town for a few days - returning only to stay one more night and fly out the next afternoon - this seems the most reasonable. We almost change our minds when we see the hundreds of people waiting at the bus stop for the Terracotta Warrior buses. It looks like a line-up for a Disney rollercoaster ride on a long weekend. It’s one of those lines that, every time you think you’ve finally joined the end of it, the security guards, who act as as line bouncers, tell you to keep walking back because you’re not there yet.

However, Xi’An public transportation is well organized in general and well-prepared for the long weekend specifically, so we only have to wait about 30 minutes for the bus. We end up on a bus that says “Terracotta Warriors” and are told yes, we go to the terracotta warriors. So we are not expecting the bus driver to shoo us off the bus at a place which is very definitely not the Terracotta Warriors site. We're supposed to transfer to another bus or take a taxi. Very confusing, though it doesn’t seem to be a scam - the whole trip only costs us about 20 cents each. Pierre, myself, six German tourists and some very patient Chinese passerby eventually figure out what bus we need to transfer to, and we arrive about 20 minutes later.

The Terracotta Warriors were discovered by a farmer who was digging a well. One of the pits actually points out the location of where the well was being drilled. The fact that it was farming land has made it very convenient for setting up the sprawling parking lot that greets visitors, and the large brick buildings that house the excavation sites are surrounded by simple gardens. We buy our 18$CAN tickets near the gate and head off to pit 3.

Around us, and in the museum near the pits, people are taking pictures of themselves and their families in front of trees, rocks, and posters describing the museum exhibits. (For a moment this reminds me of something that escapes me, and then it comes to me: hostages holding newspapers to prove they're still alive on Day X.)

During our visit, and from the guidebook, we learn that no one really knows exactly why the terracotta warriors were created. The emperor Qin Shi Huang had them made around 200 BC, presumably to use as a military force in the afterlife.

The book recommends starting at the third pit, since it’s the smallest of the three, the idea being that it lets the visitor save the biggest and best for last. I don’t know if it’s just the fact that this pit is the first one I see, but it’s definitely my favourite, and the warriors are much more impressive than I thought they would be. The lighting is great and shows off both the subtle details of the soldiers and horses the best. Few of the soldiers in this pit are intact – most of them just have empty neck holes where the neck and head would have been inserted – but those with faces and hands look incredibly lifelike.

This pit also gives a good idea as to what state some of the pits were found in.

Each coat and body are shaped differently – some are narrow-chested, others have a slight paunch and neck fat that pushes out over the collar. The book tells us that even the shoes of soldiers on bended knee have different soles.

Pit 2 gives a good idea of what the sites look like when they’re cleared down to the old roofs that sheltered the soldiers underground. Underneath each of these clay waves are soldiers and horses that haven’t been excavated yet.

Many soldiers are in pieces, as in Pit 3…

…and some are only partially excavated. Here, on the left, there’s the hind end of a horse that’s still partially buried in clay:

…though not in comparison to Pit 1.

The place is packed about 10 people deep, especially near the front. As Pierre and I work our ways to the barrier for a clearer look, I look at the view through the screens of other people’s digital cameras. I look a little out of place holding my notebook and pen rather than a camera or phone.

I love Chinese crowds – even though we’re all bumping into each other constantly and working our way forward, nobody takes the opportunity to cop a feel or do anything inappropriate.

Before seeing the pits, we watched a quick documentary which included shots of Queen Elizabeth walking down in to the main pit. I don’t generally envy royalty, but for a moment I do – getting to go down past the barriers at historic sites is an amazing perk of her job.

Pierre tells me about a German art student who painted himself and dressed up like a terracotta warrior and walked down in the pit to stand with the warriors. His outfit was so convincing that it took the security guards a while to find him.

For a minute, I envy him too.

We walk back to the bus stop, past the inevitable knick-knack shops, and we browse through the figurines and fridge magnets while we try to guess the huge animal pelts hanging on one wall.

“Wolf?” says Pierre. It’s about the right size, but the markings are different and there aren’t so many wolves kicking around China that they’d be selling pelts at a tourist gift shop.

We think about 20 more seconds and then figure it out: German shepherd.

The bus we catch back to town is full, but the hostess puts two six-inch-high stools in the center aisle for us. We ride for free.

No comments:

Post a Comment